202. Remembering The Royal Indian Navy Uprising

I'm not sure who said this, but whoever said it has certainly spoken a truth we must try to understand and follow. “Do you really believe... that everything historians tell us about women is actually true? You ought to consider the fact that these histories have been written by men, who never tell the truth except by accident.”

And the same logic applies to Indian historians who have deliberately mutilated India’s history. Dictated by Congress, the history we were taught made us stupid.

And if we try to understand the history of India, not the ancient history for which several versions are available, but the history of just the last 70 years, then I must confess, in all seriousness, that all we find is shit.

Many historical figures and numerous events have been overlooked by modern historians, if they can even be called that.

Trust me, my bold claim is justified if you take the time to get involved and do some research yourself. The surprising results will convince you to agree completely.

To make my point clear, I wish to recall one such incident—the Royal Indian Navy uprising in 1946.

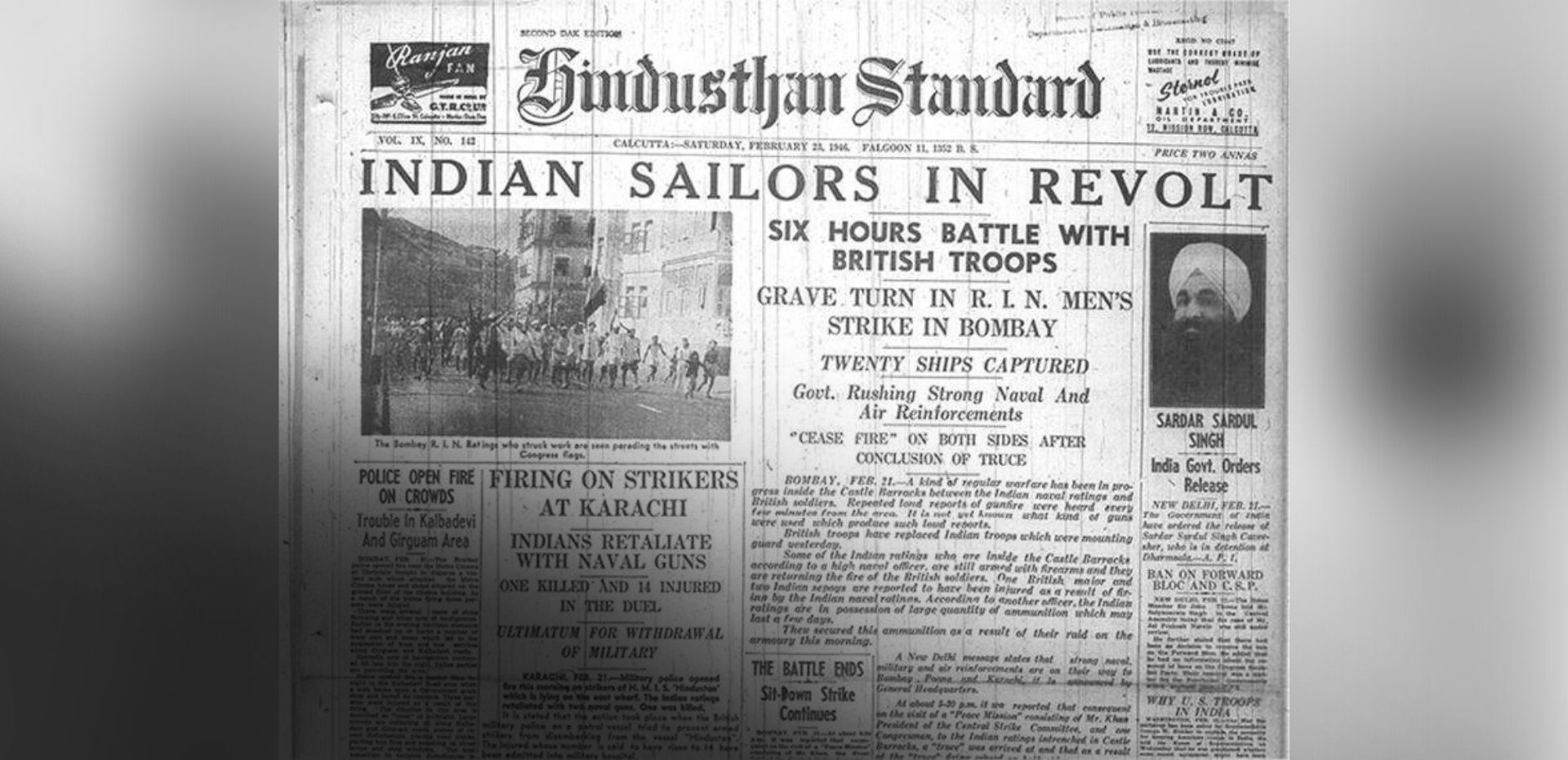

The uprising in the Royal Indian Navy (RIN) began on February 18, 1946, in Bombay when ratings (sailors) of HMIS Talwar went on strike to protest poor food, racial discrimination, and harsh conditions. The revolt quickly escalated from a hunger strike to an open rebellion against British rule.

The British called it the Mutiny, and Indian historians agreed with them. They couldn’t accept that it was an uprising.

One of the sailors was Bishwanath Bose, a man who was declared a mutineer by the British government and was mistreated even by the government that took over afterward – the Nehru government.

He was one of the many soldiers who were never recognized as freedom fighters.

The so-called historians whose books are used in schools and colleges have entirely overlooked the Royal Indian Navy (RIN) uprising of 1946. This revolt profoundly challenged the British Raj and compelled the British government to accelerate the push for independence. Called a mutiny, it was spearheaded by sailors, leading to the complete paralysis of the Royal Indian Navy.

These historians neglect to acknowledge that the British Empire's strength in Southeast Asia relied heavily on Indian contributions, especially during the Japanese invasion.

Our students should understand that events such as the Indian National Army (INA), the Bengal famine, and especially the Second World War made independence inevitable.

Indian soldiers, sailors, airmen, workers, and laborers were essential to the British victory in Burma, which revived militant nationalist movements. The period also saw Hindu-Muslim unity—evidenced by protests against the trials of INA prisoners and the heroic RIN strike of February 1946—that played a key role in pressuring the British government in London to recognize the urgency and leave India swiftly.

The RIN mutiny had a deep effect on the Raj, leading Prime Minister Clement Attlee to declare on February 19, 1946, that a cabinet mission would be sent to India. This action was arguably the most crucial move toward independence, signifying the weakening of imperial authority.

Interestingly, both Congress and the Muslim League distanced themselves from the RIN mutineers, fearing Communist Party influence. Records show that the presidents of Congress and the Muslim League in Bombay surprisingly united and offered their assistance to the police in detaining the mutineers.

MK Gandhi stated that “the mutiny had created a negative and inappropriate example for India and that a united effort of Hindus, Muslims, and others for violence was unholy.” He also said that if the RIN men pursued peaceful methods and fully informed him of their grievances, he would ensure they were “redressed.”

Yes, redressed.

This man absolutely took the very spirit of a generation and handed it over to the British government to prove his loyalty to them.

To secure his place in history books, this man sacrificed and sold India's soul, and the negativity—whether political, social, or expressed through hate and terror—that we observe in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh today stems from MK Gandhi’s unchecked ambitions.

For the British, the incidents in Bombay and Karachi brought back memories of the 1857 mutiny.

On February 23, leading seaman M S Khan, president of the Naval Central Strike Committee, declared: “Our strike has been a historic event in the life of our nation. For the first time, the blood of the men in the services and the people flowed together in a common cause. We will never forget this. Jai Hind!”

It was only in 1973, after 26 years, that the Indian government officially recognized those who served in the Royal Indian Navy and took part in the mutiny. This notable episode remains somewhat hushed and elusive in history books.