68. Discovering a Genius

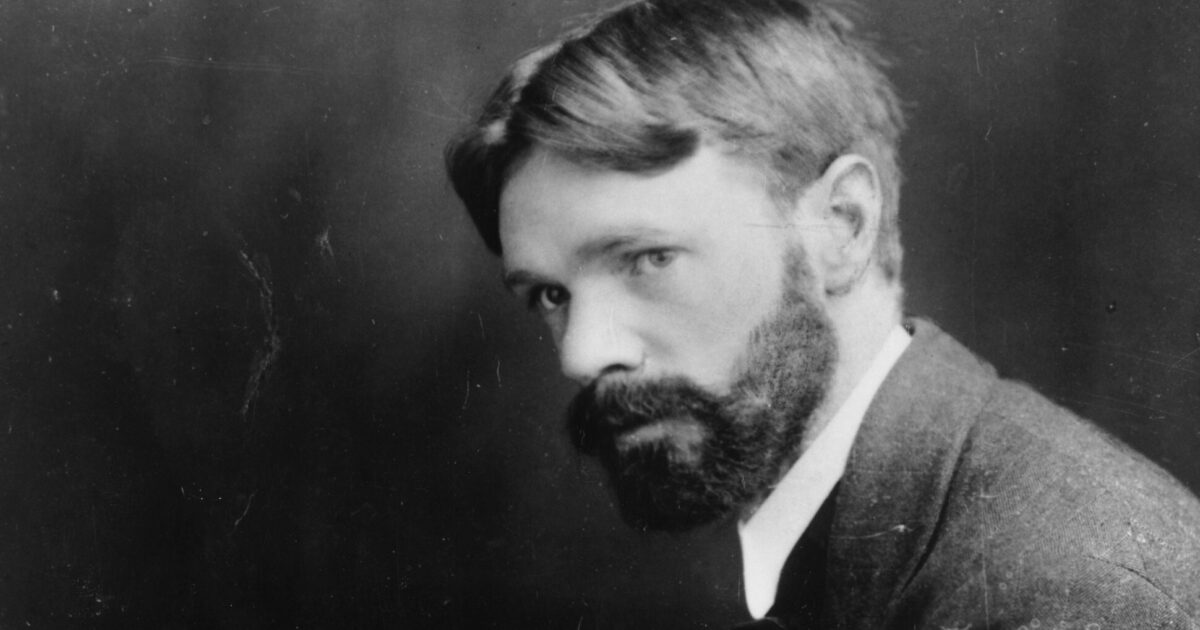

Ford Madox Ford, the then editor of the English Review, received a letter from a young school teacher in Nottingham. It said that the writer knew a young man who wrote, as she thought, admirably, but was too shy to send his works to editors. The lady had also sent a story, though she had not told the young writer that she was sending the manuscript. It was called Odour of Chrysanthemums. The lady was Miss E.T. (she had not given her full name in the letter). Later, she wrote a book, D.H. Lawrence: A Personal Record (London: Jonathan Cape), and the ‘young writer’ was D.H. Lawrence.

Let us read the first paragraph of this story: “The small locomotive engine, Number 4, came clanking, stumbling down from Selston with seven full wagons. It appeared round the corner with loud threats of speed, but the colt that it startled from among the gorse, which still flickered indistinctly in the raw afternoon, outdistanced it in a canter. A woman walking up the railway line to Underwood held her basket aside and watched the footplate of the engine as it advanced.” Nothing unusual, indeed.

However, let us examine how the editor and critic in Ford Madox Ford analyze this paragraph.

I quote: “The small locomotive engine, Number 4, came clanking, stumbling down from Selston, and at once you know that this fellow with the power of observation is going to write of whatever he writes about from the inside. The ‘Number 4’ shows that. He will be the sort of fellow who knows that for the sort of people who work about engines; engines have a sort of individuality. He had to give the engine the personality of a number… ‘With seven full wagons’…. The ‘Seven’ is good. The ordinary careless writer would say ‘some small wagons. This man knows what he wants. He sees the scene of his story exactly. He has an authoritative mind. ‘It appeared round the corner with loud threats of speed.’… Good writing; slightly, but not too arresting… ‘But the colt that it startled from among the gorse… outdistanced it at a canter’. Good again. This fellow does not ‘state’. He doesn’t say: ‘It was coming slowly,’ or-what would have been a little better- at seven miles an hour.’ Because even ‘seven miles an hour’ means nothing definite for the untrained mind. It might mean something for a trainer of pedestrian racers. The imaginative writer writes for all humanity; he does not limit his desired readers to specialists ……… But anyone knows that an engine that makes a great deal of noise and yet cannot overtake a colt at a canter must be a ludicrously ineffective machine. We know then that this fellow knows his job. ‘The gorse still flickered indistinctly in the raw afternoon.’ … Good too, distinctly good. This is the just-sufficient observation of Nature that gives you, in a single phrase, landscape, time of day, weather, and season. It is a raw autumn afternoon in a rather rural countryside. The engine would not come round a bend if there were not some obstacles to a straight course – a watercourse, a chain of hills. Hills, probably, because gorse grows on dry, broken-up waste country. They won’t also be mountains or anything spectacular, or the writer would have mentioned them. It is, then, just ‘country’. Your mind does all this for you without any ratiocination on your part. You are not, I mean, purposely sleuthing. The engine and the trucks are there, with the white smoke blowing away over hummocks of gorse. Yet there has been practically none of the tiresome thing called descriptive nature, of which the English writer is, as a rule, so lugubriously lavish… And then the women come in, carrying her basket. That indicates her status in life. She does not belong to the comfortable classes.”

Wonderful! Isn’t? That is called criticism, bare all, share all. I personally find that most of the reviews published in magazines (yes, including this one) are pretty dull, biased, and overly praising. But I’ve an explanation for my readers. Since I don’t pay my reviewers, I don’t have any expectations, so I let it go as it is. And how serious a writer he was, I quote Ford again to make my point very clear.

Ford writes: “He brought me his manuscripts-those of The White Peacock and Sons and Lovers. And he demanded, imperiously, immensely long sittings over them…. Insupportably long ones. And when I suggested breathing spaces for walks in the park, he would say that wasn’t what he had sacrificed his Croydon Saturday or Sunday for. And he held my nose down over this passage or that passage and ordered me to say why I suggested this emendation or that. And sometimes he would accept them, and sometimes he wouldn’t, but always with a good deal of natural sense and without prejudice. I mean that he did not stick obstinately to a form of words because it was his form of words, but he required to be convinced before he would make any alteration.”